Here is the latest news report about the passing of a blues legend:

Here is the latest news report about the passing of a blues legend:

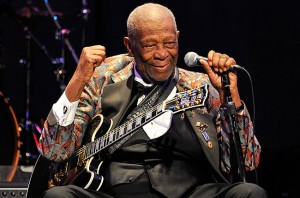

B.B. King, “the King of the Blues,” whose stinging guitar solos and husky, full-throated vocals made him an international music icon and the most commercially successful performer in blues history, died Thursday in Las Vegas, his attorney told the Associated Press. He was 89.

The winner of 15 Grammy Awards, the most in the blues genre, Mr. King achieved his success despite having only one Top Twenty single, “The Thrill Is Gone,” which reached number 15 on the pop charts in 1970. His distinctive singing voice, which ranged with ease from commanding roar to beseeching falsetto, has for decades been part of the soundscape of music lovers the world over.

He earned that place through countless performances of blues standards like “Everyday I Have the Blues” and “How Blue Can You Get” or such compositions of his own as “Rock Me Baby,” and “Sweet Little Angel.”

Mr. King was a key transitional figure between the blues and rock ’n’ roll. Where such older bluesmen as Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf helped inspire young English and American rockers in the ’60s, Mr. King influenced them directly. His single-note guitar style, with its heavy vibrato, bent notes, and near-vocal tone provided a model for such rock guitarists as Mike Bloomfield, Eric Clapton, and Stevie Ray Vaughan.

Ironically, Mr. King’s style sprang from an inability to play slide guitar. He strove, with unrivaled success, to achieve slide effects using just his fingers. “I wanted to sustain a note like a singer,” Mr. King wrote in “Blues All Around Me,” his 1996 autobiography. “By bending the strings, by trilling my hand — and I have big fat hands — I could achieve something that approximated a vocal vibrato. . . . I was looking for ways to make my guitar sing.”

“I don’t think there’s a better blues guitarist in the world,” Clapton said of Mr. King in a 1968 interview with Rolling Stone magazine. The two collaborated on a double-platinum recording, “Riding with the King,” in 2000. Mr. King’s affinity for rockers had been proven earlier when he joined with U2 on “When Love Comes to Town,” for which they shared an MTV Video Music Award” in 1989.

In 2003, Rolling Stone ranked Mr. King No. 3 on its list of the greatest guitarists of the rock era (behind Jimi Hendrix and Duane Allman). One can endlessly debate such rankings. What’s beyond dispute is that Mr. King’s instrument, Lucille, was the world’s most famous guitar.

She got her name in 1949 when Mr. King was performing in Twist, Ark. A fistfight knocked over a kerosene burner, which set the building on fire. Mr. King braved the flames to rescue his guitar. “Damn,” he heard a patron say, “you wouldn’t think two guys would near kill each other over a gal like Lucille.” As of 1996, there had been 17 Lucilles in all.

From Twist juke joints to Carnegie Hall, Mr. King spent decades performing before audiences. Some of his best-known recordings, including “Live at the Regal” (1965) and “King and Bobby Bland … Together for the First Time … Live” (1976), were made in concert. Mr. King ran James Brown a close second for the unofficial title of Hardest-Working Man in Show Business. He played 342 one-nighters in 1956 and well into his 70s averaged 250 appearances a year.

“I enjoy it,” Mr. King said of his touring in a 2004 Globe interview. “I’ve missed 18 days in my 57 years of playing. If they book me, I’ll be there.”

Mr. King’s hard work was evident every night on his face. In his autobiography, he joked that his first wife “used to call me ol’ lemon face because of my facial contortions when I play Lucille. I squeeze my eyes and open my mouth, raise my eyebrows, cock my head, and God knows what else. I look like I’m in torture when, in truth, I’m in ecstasy.”

Mr. King slowly worked his way up from the so-called chitlin circuit, playing before largely African-American audiences, to trading quips with Johnny Carson. (Mr. King was the first bluesman to perform on the “Tonight” show, in 1970.) He crossed over to mainstream popularity as had no other blues performer. Mr. King acted or appeared as himself in several movies, on television sitcoms, and even a soap opera (“General Hospital”).

Mr. King’s popularity extended to business. “B.B. King has turned into a conglomerate,” he wrote with some bemusement in his autobiography. Mr. King endorsed many products over the years, from Burger King to Budweiser, and under his name marketed guitar strings, leisure wear, and even salsa and barbecue sauces. There’s a chain of B.B. King blues clubs.

A key to Mr. King’s widespread popularity was his being no blues purist. He drew on many musical sources. The jazz guitarists Charlie Christian and Django Reinhardt strongly affected his playing, though the biggest influence on him was the blues singer-guitarist T-Bone Walker. Mr. King offered a slick, even show-biz presentation. Whenever possible, he included horns in his band. He recorded “The Thrill Is Gone” with a string section.

Mr. King was an unabashed crowd-pleaser. There was nothing dangerous or threatening about him. His obvious affability and the frequent good humor of his music were central to his success. Indeed, Mr. King is responsible for what may be the most slyly witty lamentation in all American music, “Nobody loves me but my mother/And she could be jiving, too.” His work has no hint of the menace of a John Lee Hooker or the ferocity of Muddy Waters.

“From the day I’d started out,” he wrote in “Blues All Around Me,” “I’d been called a rhythm and blues artist. I thought that description fit me. But somewhere in the sixties they droped the ‘rhythm,’ and I became blues only. . . . I think the original label still says it best.”

Riley B. King (the middle initial doesn’t stand for anything) was born on Sept. 16, 1925, in Itta Bene, Miss. He became “B.B.” during the late ’40s, as a Memphis disc jockey, when he was known as the Beale Street Blues Boy. His parents, Albert Lee King and Nora Ella (Farr) King, were sharecroppers. They separated when Mr. King was 4. His mother died when he was 9. He lived on his own for several years, until rejoining his father.

At 12, Mr. King bought his first guitar. It cost him $12. “Never have been so excited,” he wrote six decades later. “Couldn’t keep my hands off her.” Mr. King sang in a gospel quartet (its influence would remain audible in his singing) and sang on street corners. He discovered the blues, in the person of his first cousin once removed, Bukka White, and, via records, through “the open cry of Blind Lemon [Jefferson] and the sweetness of Lonnie Johnson.” He began to go into the nearby town of Indianola on Saturday nights to stand at a nightclub peephole and listen to such visiting performers as Count Basie and Louis Jordan. “I believe I listened harder than anyone in the history of listening,” he later wrote.

Dropping out of school in 10th grade, Mr. King worked as a farm laborer, which earned him an exemption from military service during World War II. He married Martha Lee when he was 18. The marriage ended in divorce, as did a second marriage, to Sue Terry.

Mr. King did not disguise his fondness for the opposite sex. “I’ve been lost in the love of women my whole life,” he once wrote. Mr. King fathered 15 children by 15 different women (his marriages were childless). “That both enriched and complicated my life,” he wrote in “Blues All Around Me.” He was proud of the fact he provided financial support for all of his children and never contested their paternity.

After World War II, Mr. King decided on a musical career and moved from Indianola to Memphis. “It was about 130 miles north,” he said in a 1967 interview with jazz historian Stanley Dance, “but to me that was like going to Europe.”

Mr. King began to earn a name for himself as a performer and DJ. “I’d see all these discs by all these artists from all these labels,” he later wrote, ‘and think to myself, I’m out of the cotton field and in the music field!” He made his first recording in 1949 and had his first hit, “Three O’Clock Blues,” in 1951.

Mr. King was the recipient of honorary degrees from Yale University and the Berklee College of Music. He was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1987. That same year, he received a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award. George H.W. Bush presented him with a Presidential Medal of the Arts, in 1990. He was a Kennedy Center honoree in 1995 and in 2006 was a recipient of the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor.

The B.B. King Museum and Delta Interpretive Center opened 2008 in the Indianola cotton mill where Mr. King once worked.

Mr. King frequently gave free concerts for prisoners. Two of his best-known recordings are “Live in Cook County Jail” (1970) and “Live at San Quentin” (1990). With attorney F. Lee Bailey, he began the Foundation for the Advancement of Inmate Recreation and Rehabilitation.