Guitarist Bob Wolfman has been respected for his advanced musical skills for a long time. He was already a Manhattan session player before he finished high school. Yet, he should be even more respected for his never ending quest for self-improvement. Despite his ability to play fast chords over complicated scales, Wolfman never rests on his laurels. At heart, he is still a student of the guitar, voice, music, teaching, and recording. Whatever his latest project might be, listeners can bet their last dollar that Wolfman will be stepping up his game, taking it to an even higher level.

Guitarist Bob Wolfman has been respected for his advanced musical skills for a long time. He was already a Manhattan session player before he finished high school. Yet, he should be even more respected for his never ending quest for self-improvement. Despite his ability to play fast chords over complicated scales, Wolfman never rests on his laurels. At heart, he is still a student of the guitar, voice, music, teaching, and recording. Whatever his latest project might be, listeners can bet their last dollar that Wolfman will be stepping up his game, taking it to an even higher level.

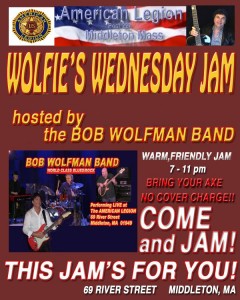

Wolfman recently started a Wednesday night jam at in Middleton, Massachusetts. That venture, too, is an indulgence in self-improvement, a low key one. Wolfman, in between managing equipment and jammers, observes quite of bit of technique he wasn’t already familiar with.

“It never ceases to amaze me that I learn a lot from some of the most subtle, unobvious things that I’ll hear somebody do,” he said. “I’ll hear one of my students do something that they just do or they picked up somewhere. The jammers too. We had a band sit in and play last night. They did four songs. I hear somebody do something, and it’s not necessarily even a technical thing. It’s not necessarily a music theory thing, like he used a certain scale or certain chords. It may just be the way they present something, the sound that they have. I learn from this. I gain insight. I grow from that. It’s something I can use. Like George Benson says, ’If you don’t want me to steal it, don’t play it.’”

Wolfman, already a Manhattan session player in high school, and beginning to learn jazz fusion, and touring the country, learned the hard way that he wasn’t playing as well as he needed to be to move forward. A mentor named Hiram Bullock told him that he needed to go to school to learn theory. Bullock told him “You have the best chops, the fastest hands, the best ears, better than anybody but you need to get your jazz chops together in terms of reading and in terms of theory.”

Wolfman admits to becoming defensive, upset, but the next morning he woke up and made his decision. He moved to Boston five to six weeks later to attend Berklee College Of Music. Wolfman was still going back and forth to New York City to keep his name in circulation. Eventually, the traveling became tiresome and many of his New York City band friends were getting heavily involved with serious drugs. In fact, Hiram eventually died of a crack overdose.

Wolfman admits to becoming defensive, upset, but the next morning he woke up and made his decision. He moved to Boston five to six weeks later to attend Berklee College Of Music. Wolfman was still going back and forth to New York City to keep his name in circulation. Eventually, the traveling became tiresome and many of his New York City band friends were getting heavily involved with serious drugs. In fact, Hiram eventually died of a crack overdose.

After graduating from Berklee in 1980, Wolfman began working on starting his own school, opening Wolfman School Of Music in 1983 before reopening in 1986 in a larger commercial space in Arlington, Massachusetts. With 35 instructors on his staff, Wolfman’s school offered a lot, guitar, bass, drums, saxophone, voice, blues, harmonica, and a whole range of theory courses. His school also possessed a fully equipped recording studio and taught audio engineering at all levels. Aside from teaching, they recorded and produced hundreds of bands and singer-songwriters. Berklee College of Music made it their first official prep school.

Having his own school also contributed to his own growth as a musician. “I got to extract what was the most important aspect I feel of music in terms of performance and what I needed to know as a musician,” he said. “I had some great instructors working for me. I had Mike Williams who’s been a teacher at Berklee for many years. I had guys who graduated from New England Conservatory or Berklee. So, I got to learn a lot from being around a lot of really good musicians, in terms of what were their influences, who they studied with. I also wrote a lot of curriculum for the school, so it compelled me to synthesize everything I had learned into cogent and effective learning programs.”

Between 1980 to1984 Wolfman formed and maintained a fusion band called Elan Vital that played, among other local venues, Jonathan Swift’s at Harvard Square and featured world class musicians. “It was very technical music,” Wolfman said. “It was very precise. It was very developed. It was very sophisticated music. It was complex, but it grooved. It was high energy.” Elan Vital played TV, radio, and many name venues. “Every gig was pretty memorable,” he continued. “The audiences loved it. The venues loved it. We actually made some money.”

And talking about having to step up his game on stage; Wolfman has been playing with his mentor Larry Coryell since he was 18 years old, when he became his protégé. “To this day, if I have a gig with Larry at The Bull Run, I will practice my ass off, harder than I’ve ever practiced before. I will play ten to 12 hours a day, and my hands will not hurt but be sore.”

And talking about having to step up his game on stage; Wolfman has been playing with his mentor Larry Coryell since he was 18 years old, when he became his protégé. “To this day, if I have a gig with Larry at The Bull Run, I will practice my ass off, harder than I’ve ever practiced before. I will play ten to 12 hours a day, and my hands will not hurt but be sore.”

Wolfman also works with Chick Corea and many other great jazz musicians, so he cannot afford to let his standards slip. After mastering technique, though, Wolfman looks beyond skill. The musician must also look at the entire impact he makes on his audience, making it about feeling.

“Technique is a conduit for emotion,” he said. “It’s a way to get emotion across to your audience. So, now when I practice for a gig with Larry, or somebody like that, it’s not just about speed and chops and technique. It’s about what am I saying. It’s much more about the melody. I’m trying to create as much or more emotional impact with three notes as opposed to 30.”

For feeling, Wolfman has a huge, huge background in blues. There are a lot of jazz guys who cannot bend notes and get a vibrato like the classy blues players, indicating the extent of Wolfman’s talent. Sometimes, though, Wolfman gets frustrated by people who think he only plays jazz or think he only plays blues, people who pigeonhole him as solely a player of one genre.

“If I’m a good musician and I’m good at jazz, why can’t I play jazz and why can’t I plays blues and why can’t I play rock? Why can’t I play anything I want?”

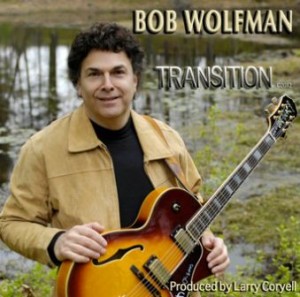

Wolfman’s latest of three albums, Transitions, was an improvement of his other two fine releases. The improvement, was owed, in part, to the personnel he used. Larry Coryell produced it and played second guitar. Victor Bailey, who replaced Jaco Pastorius in Weather Report and at age 19 was labeled the greatest electric bassist on the planet, played bass on Transitions. Drummer Kenwood Dennard was another player who forced Wolfman to step it up during the recording process. Dennard has played with Miles Davis, Herbie Hancock, Dizzy Gillespie, Pat Methanie and many others greats.

Wolfman’s latest of three albums, Transitions, was an improvement of his other two fine releases. The improvement, was owed, in part, to the personnel he used. Larry Coryell produced it and played second guitar. Victor Bailey, who replaced Jaco Pastorius in Weather Report and at age 19 was labeled the greatest electric bassist on the planet, played bass on Transitions. Drummer Kenwood Dennard was another player who forced Wolfman to step it up during the recording process. Dennard has played with Miles Davis, Herbie Hancock, Dizzy Gillespie, Pat Methanie and many others greats.

“They inspired me to play better, sing better,” Wolfman said. “Larry’s purpose as producer of this record was to showcase me not only as a really good guitarist or singer or composer but my versatility. We do ‘Born Under A Bad Sign,’ classic blues tune. We do the old standard ‘Guess Who I Saw Today.’ It’s like a Mel Torme/Frank Sinatra tune.’”

Coryell’s second purpose was to show Wolfman’s range and depth as well. “It’s very all over the map. There’s a lot of different styles,” he said.

Wolfman will always be striving for higher achievement, no matter if he’s playing a blues show, a rock show, or a jazz concert. He will need all of his strength for his next visionary project.

“I want to put out a lot more records. I want to record a lot more, and I want to tour with my own about the U.S. and Europe and other places,” he said. “I want to do my original material. It’s going to be more blues-rockie. It will my music, so it will have all my influences, including jazz, some gospel, some soul, some R&B. It will be a little funky sometimes. It will be really strong guitar playing. It will be really good vocals. It will be really danceable, high energy. I want to get major recognition. I want to be national within say 12 to 15 months, which is a tall order, but I think it can be done.”